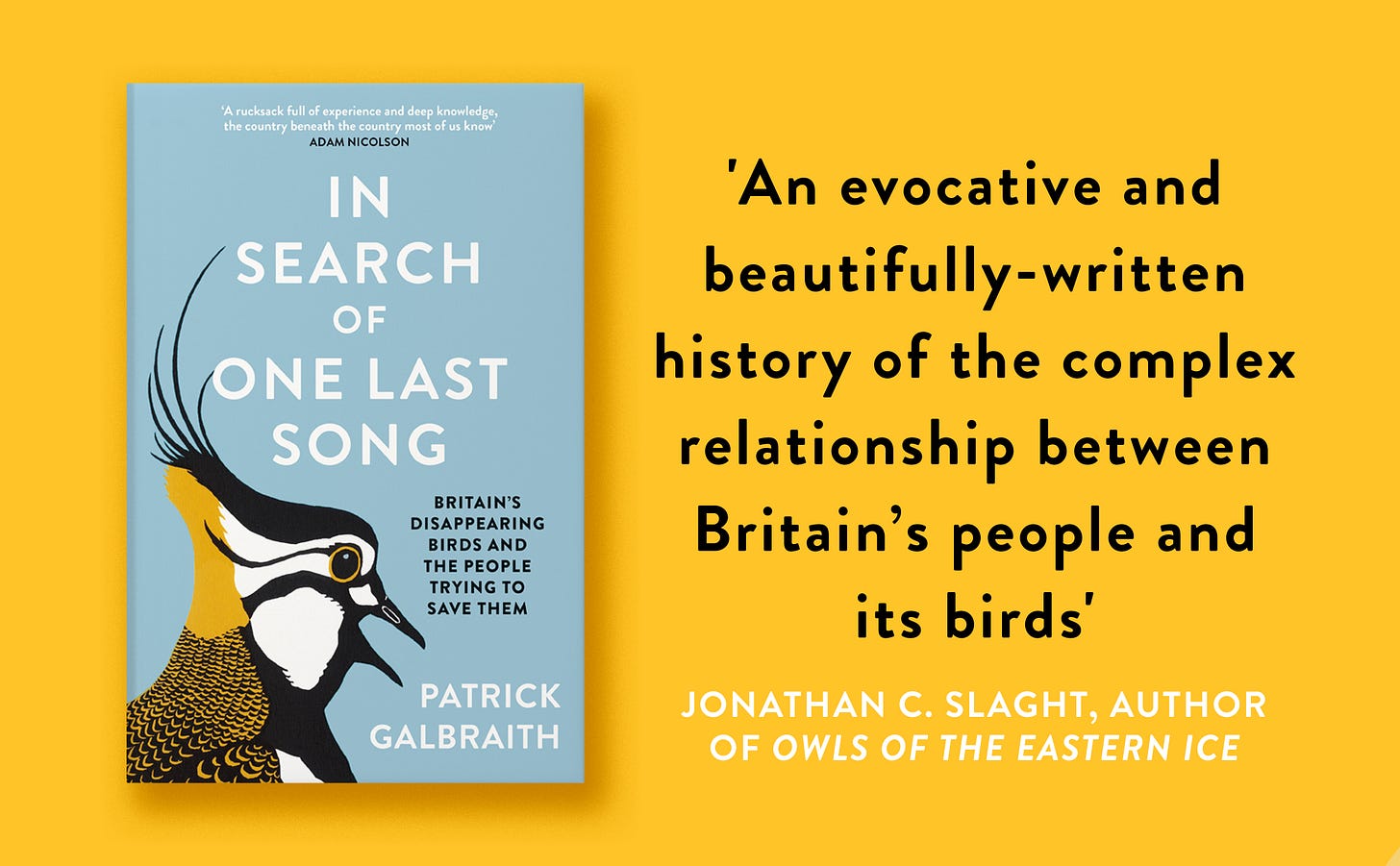

A bell tolls for the turtle dove

An excerpt from Patrick Galbraith's In Search of One Last Song: Britain's disappearing birds and the people trying to save them

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been talking to various writers about their work and how they ‘do it’. These conversations will all appear on our new podcast, Tell me how you write. So far, I’ve chatted to Luke Turner and Timothy O’Grady, whose novel Monaghan will be published by Unbound in June. My colleague, Sadia Nowshin, has spoken to the poet and Boundless contributor, Katrina Porteous, and she will shortly be talking to the novelist, Fiona Williams.

In the main, these conversations are about process. Luke Turner, it transpires, writes for two hours a day, usually after he’s had a cup of tea at around five o’clock. Katrina, it turns out, spends a lot of time watching and listening, before she puts pen to paper. She watches the birds and listens to the land and the sea. Timothy O’Grady, whose prose style is remarkable, says that for him writing tends to start with reading. You can’t, he believes, write ‘good stuff’ unless you read ‘good stuff’. He is particularly keen on Gabriel García Márquez.

As well as talking about ‘process’, I like to ask writers about their relationship with their work. Do they flick admiringly through their books, in a state of satisfaction, or can they hardly bear to read them at all? Inevitably, their thoughts have led me to think about my relationship with my own writing.

About two years ago, I really didn’t enjoy going back over anything I had written. It wasn’t that I thought it was terrible. It was more that I was pained by always thinking it could have been much better: every sentence, every image, every thought. Why hadn’t it struck me, at the time, to do it ‘like this’ instead of ‘like that?’

And then, in the autumn of 2022, I went to the Wigtown Book Festival to talk about my first book, In Search of One Last Song, which tries to understand Britain’s relationship with birds. When some of them become extinct, as a number of them in England soon will, what will actually be lost? The lady who was interviewing me asked, while we were having coffee before the event, if I could read something from the book. It wasn’t a particularly welcome request but of course I said yes and after she introduced me to the audience I read the very short passage below. When I finished, there was a moment of quiet, and I looked round to see that she was crying. It wasn’t, she said later, about the birds really. It was about, ‘the meaning’ of the birds and ‘the beauty of it’. I suppose I don’t really know why it spoke to her.

I think that moment was the start of a process of realising that dissatisfaction is simply the writer’s lot. Perhaps the day that a writer thinks ‘yes, that is good. That really is something’, is the day a writer has become as good as they ever will.

A bell tolls for the turtle dove

We are perched side by side on plastic sun-bleached deckchairs, the blue-eyed farmer and me, in a rusty old shipping container. It is May, not yet mid-morning, but it is the driest May on record and the large metal box will soon be too hot. ‘Turtle doves have been part of my life as soon as I could walk,’ Graham Denny tells me brightly. ‘I’d wander out into the yard and there’d be cattle down both sides, you’d have pigs, and you’d come and there’d be turtle doves sat in the yard. Dad would get handfuls of rolled wheat and rolled barley and he’d throw it on the ground’ – he gestures towards the dry earth in front of us – ‘and the turtle doves would come and you’d see them there with the sparrows feeding quite merrily.’

He stops talking to blow on his tea and then tells me, hurriedly, that his great grandfather bought Brewery Farm, the 200-acre Mid-Suffolk plot we’re sitting on, on the old road to Norwich. We are partly hidden by some canvas webbing that Graham has hung across the front of the container, and about 50 yards out, a few handfuls of cracked seed are scattered across the ground. It was Graham’s grandfather who first took him to feed the doves, when he was a little boy, and he’s done it ever since. So far, possibly due to storms in the Mediterranean, only a small number of the birds have returned from Africa, but we are hoping one of them might flutter down in front of us to feed before they head up into the trees for the day, in search of shade. Graham tells me he can’t remember a time when he didn’t love turtle doves, but that the more their numbers have diminished, the stronger that love has grown. It has been exactly a fortnight since the first dove of spring arrived back at Brewery Farm, which was just thirteen days after Graham’s father died. ‘Heard it purring in the hedge and I just howled and I howled. Turtle doves is something I shared with my dad my whole life and now, when my own boy comes up from his mum’s, I make sure he feeds them.’

Patrick Galbraith is the Editor of Boundless. His first book In Search of One Last Song, was published in 2022 and his second book, Uncommon Ground, will be published by William Collins on April 24.