An archivist collects herself

Jenifer Monger revisits old diaries and recreates a new the past

I am an archivist, and I love what I do. Contrary to much popular opinion, archives are not 'dusty' or 'forgotten' — in fact, usually quite the opposite. I am the steward of others' histories, others' lives; access to archives brings the past vividly alive. But what of the life of the archivist herself?

During the Covid pandemic I became a full-time digital/remote archivist, after working predominantly with paper based collections. By December 2020, I was hungry for that tactile experience of conducting research in the collections and discovering new stories. But I had no idea when my place of work would reopen — so an alternative was to teach myself how to bind books as a way to stimulate an old passion of mine. It occurred to me that, away from my institution’s shuttered library and collections, I had my own archives which I could use to study myself as a research subject.

A journal sitting on the bottom shelf of a tall bookcase caught my attention. I hadn’t touched it for years. I created it in 2001 while in Italy. Staring at just the binding itself as it sat on my shelf, I could recall the colours, smells, and tastes of the country.

For a week, I stared at it and held back: I only understood why when at last I broke through my own reserve and held it in my hands. As I began to read, the excitement that I originally felt evaporated. I considered how many wonderful memories never got recorded; one of the mysteries of an archive, that so much of life will never make its way onto paper. But there was something else too, something more challenging to grasp.

This journal was created to document my involvement with an art history college course when I was in my mid 20’s, focused on Renaissance art and architecture throughout Florence and Rome. Throughout the journal I documented the artwork and architecture I saw by incorporating handwritten text, photographs, postcards, and drawings. But this wasn’t a private journal: it was an ‘official record’ of my trip meant to be seen by the Art History professor, to read, review and grade when the trip was over. After it was returned to me, it became an endearing symbol of my first trip abroad. Yet it had remained unopened for 20 years.

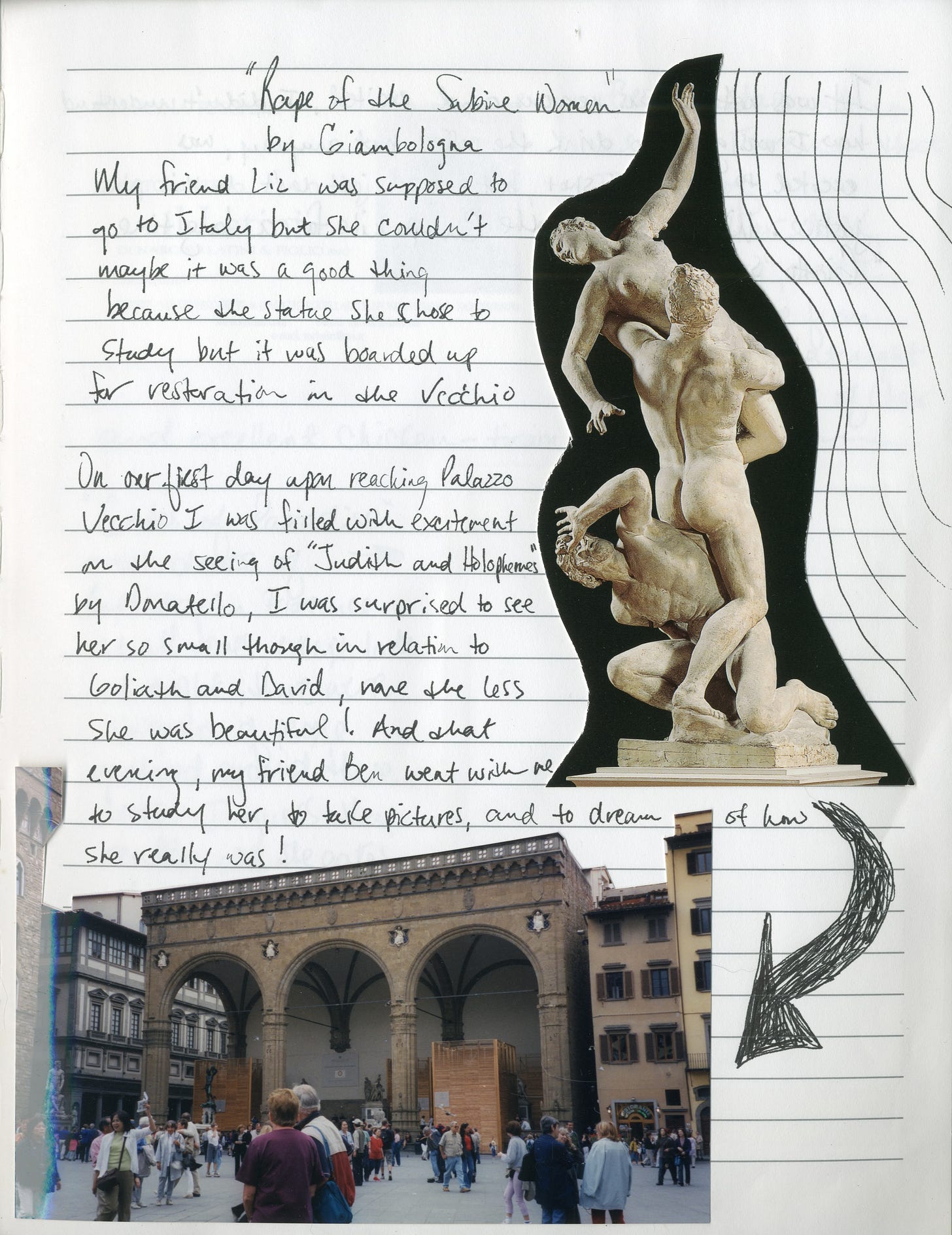

This cherished object was now calling up some unpleasant memories On one page included a postcard of the sculpture ‘Rape of Sabine Women’ by Giambologna. In the commentary on the journal page, I describe how my friend was supposed to write a paper about this sculpture, but when I arrived in Florence and visited the Loggia dei Lanzi — the outdoor museum where the sculpture was located — I found it boarded up.

I remembered purposefully writing these words as a subtle way of telling my professor that he hurt my friend. I wanted him to feel shame. Prior to the trip I learned from my classmate and friend that they felt they couldn't go because the professor was hitting on her. I went with her to report it, but her complaint was swept under the rug. The incident was downplayed and the advisor didn’t want to make a fuss. I ended up going to Italy, but my friend stayed home and we never saw each other again.

Over the past three years, I’ve found a way to reconnect with that formative but difficult time through the journal. In grappling with my memories of it I have also rediscovered it. I’ve been sifting through the various identities of myself now associated with it: creator, archivist, and researcher. These identities hold differing perspectives that were often at odds with one another. But each identity had a common goal — deal with that journal and the memories that bubbled to the surface.

I decided to digitise the journal. The archivist in me was adamant about it remaining as it was, and digitising it would give the creator in me room to breathe life into it — though I wasn’t sure how exactly. While my intentions were to keep the journal intact, I also wanted to lessen the impact the professor had on it: to make something that had been an ‘official document’ into something more personal and true. And then a fellow Paperologist introduced me to a technique called Grangerizing. She explained that in the 19th century, people would remove the binding of a published book, add illustrations to compliment the book, then have the ‘new’ book rebound.

In 1769, Reverend James Granger published the Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution. His book was a catalog of all the known English portraits arranged by name, class and period. Granger included blank leaves to let collectors add additional prints and for readers to take notes in the book. The first ‘extra-illustrated’ version of Granger’s book was created by Richard Bull, who included 14,000 prints — expanding Granger’s original four volume set of A Biographical History into 36 volumes. He started the craze which evolved into a bibliophile subcultural pastime.

Extra-illustration, as it later became known, was an elite practice of book-breaking. A variety of books were re-used: biographies, travel, Shakespeare, the Bible. A binding of a book was broken, then the illustrator gathered works of art on paper that could serve as personalised ‘extra’ illustrations to the text in their foundational book. This was guided by personal interests and sensibilities — the connections the individual wanted to make between the original and what was pasted in.

This practice affords the creator the ability to work in a personal creative space that feels performative, but there’s no audience — it’s just for the creator. I began to see ways in which combining the creator and archivist no longer felt antagonistic. This was an artform which took time and precision. Custom ‘windows’ are created in the book’s pages to house the additional material, work of painstaking accuracy; when finished the individual pages are bound into a new book. Feeling the pages, you wouldn’t know they are two separate pieces of paper pasted together.

This research was the fuel I needed to understand my next steps with my own journal. With the journal a source of emotional unrest, my approach to it became a process of re-appraisal. I had been so fearful of ruining my journal but now, I was owning it, and using my own research to improve it, to process and collect myself. So, one night I took an Exacto knife and freed my journal from bondage, scoring the binding off of it and separating the pages from one another.

Then came the mania I had only read about — the frenzy of collecting the extra images to illustrate books. I scoured eBay matching vintage postcards to the images I included in my journal. I bought old Italy travel guides and ripped them up to add maps, features and locations to what I had already included in the original. I gathered as many postcards and other images of the Sabine women that I could. And then there was the original page that detailed why my friend had not been able to go on this trip: I knew I could no longer keep it intact. I felt that part of the healing process was to disrupt and deconstruct that page. This was no longer about holding onto what happened and enshrining it in a new page. This needed to be imbued with new meaning.

Extra-illustrating my journal has allowed me to create additional layers, depth, and meaning to what I’d made 22 years ago. I’ve been able to open up, expose, admit, acknowledge and see this past in a new way as well as forge ahead and rebuild the journal in a way that honours both my friend and myself. I don’t go here lightly, but this repurposed and resurrected object is really imbued with some radical fuck you girl power. That professor, I like to think anyway, might not have looked at Judith beheading Holofernes in quite the same way ever again.

In 1967, Ulric Neisser published Cognitive Psychology — a seminal work, and one that led to his being considered the father of the field. He likened aspects of remembering to paleontology. He stated succinctly that ‘out of a few stored bone chips, we remember a dinosaur.’ And so it has been for me with my Italian journal. I excavated my own historical record to express what I believe, what I recall based on my memories and the triggers and pain-points I found in my own record. It was more challenging than I ever bargained for to engage with my own primary resource, thinking critically about it, relating it to my personal history, grappling with the complexity of who I am.

Jenifer is a professional archivist at a private university in New York. She’s been in the cultural heritage field since 2007, sharing knowledge of collections and fostering a deeper understanding of history. Her scholarship consists of a cross pollination of disciplines which is where she finds the most intellectual comfort