Bedrock, Coleridge's shame, and the inevitability of errors

With Erica Wagner and Tom Hughes

There’s an old joke in the world of books which runs something like ‘the very best way to find errors in your manuscript is to have it published and then to head down to your local bookshop.’ Invariably, right there on the first page you turn to will be some absolute horror. So it was that I found myself in Waterstones’ some weeks ago when I caught sight of my new book over with the other runners and riders in hardback non-fiction. I’m not sure why I did it really but I turned to the Scottish chapter and there it was. Rather than writing that the distance between mainland Scotland and the Isle of Lewis is some 65 miles, I instead have it down as 165. Quite how this ridiculous error evaded us all and ended up inked into many copies, none of us know but it’s there alright. And for the rest of the afternoon, as I wandered around West London, it pained me.

It’s not, I’m sorry to say, the only error that lives in those pages. There’s one mistakenly repeated sentence, the odd stray comma, and a friend currently won’t speak to me because I accidentally misgendered his dog. He has promised that no legal action will be taken if a paperback amend is made.

Errors are a funny thing – they are deeply annoying and yet, they are testament to the material being produced by a living, breathing person. They make it artisanal in some strange way. They are proof of a journey being undertaken and of a not-always-successful attempt to stay on track.

There will be more in there. No doubt about it and I’ll catch a few of them before the paperback goes to press but some will remain and there will be errors in almost every single new book that hits the shelves of that very same West London Waterstones this year. Does it matter? Possibly not. There’s a charm of sorts in a typo.

Patrick Galbraith

Editor

Too dreadfully dreadful

Tom Hughes, the author of A Shattered Idol, which has just been published by the independent publisher, Marble Hill. shines light on a lost Victorian scandal

Aristocratic misbehaviour, to be sure, was regular entertainment for the great Victorian public. “Earls and girls,” you know. Many of the malfeasants were from the bawdy set of peers orbiting the rotund figure of the Prince of Wales. Queen Victoria was never amused. Thus, the Coleridge sensations, detailed in my new book, A Shattered Idol – The Lord Chief Justice & His Troublesome Women, were unique. For most of a decade, the public craved every detail of whatThe World called “one of the most despicable scandals ever enacted in an English household.”

John Duke, the first Baron Coleridge, was Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales from 1880. Such a grandee is impossible to envision today. “In all externals, he was perfect,” according to the Edinburgh Review. He loved his ceremonial “toggery,” he called it, embellishing his robes with sashes and ruffles of his own design. Feared on the bench, Lord Coleridge reveled in deprecation and “polished pungency,” delivered with his customary seraphic smile. He likely inspired the oft-portrayed arrogant judges who plagued poor Rumpole and his cowering ilk. A great nephew of the immortal poet, in private life, Coleridge consorted mostly with divines and sages. He read only The Times, never went to the races, and ignored the theatre. In sum, according to Dublin’s Freeman’s Journal in 1884, the “Pecksniffian aroma” which pervaded Lord Coleridge’s public character explained the “malicious interest taken in the exposure of his private relations with his family.”

In his sixties Coleridge was a widower with three sons; he lived with his unmarried 35-year-old daughter Mildred, who kept his homes in Sussex Square and Devon. Mildred never grumbled. It was the ordained role of the eldest, unmarried daughter. She had her pin money, her beloved pianoforte, and her “expectations.” (£300 a year, worth a quarter-million quid today per measuringworth.com!) Mildred was active in the Victoria Street Society — A-listers of the time who drove the rising antivivisection movement in Britain. There, she came met Charles Warren Adams, editor of The Zoophilist. They were ill-matched. Mildred was tall, like her father, a bit stooped, bespectacled, and was described cruelly as “devoid of personal attraction.” She was, her family believed, “not as others.” Adams, however, was a blustering, peevish fellow, “hairy and bejeweled,” and chronically skint. They worked closely together, daring to publicly use their first names around the office. An undue familiarity at the time, to be sure, but when interrupted in a darkened room, the relationship had to end. Her father and her three brothers were adamant but Mildred sulked.

An excerpt from Erica Wagner's Chief Engineer

Tom Hughes, the author of A Shattered Idol, which has just been published by the independent publisher, Marble Hill. shines light on a lost Victorian scandal

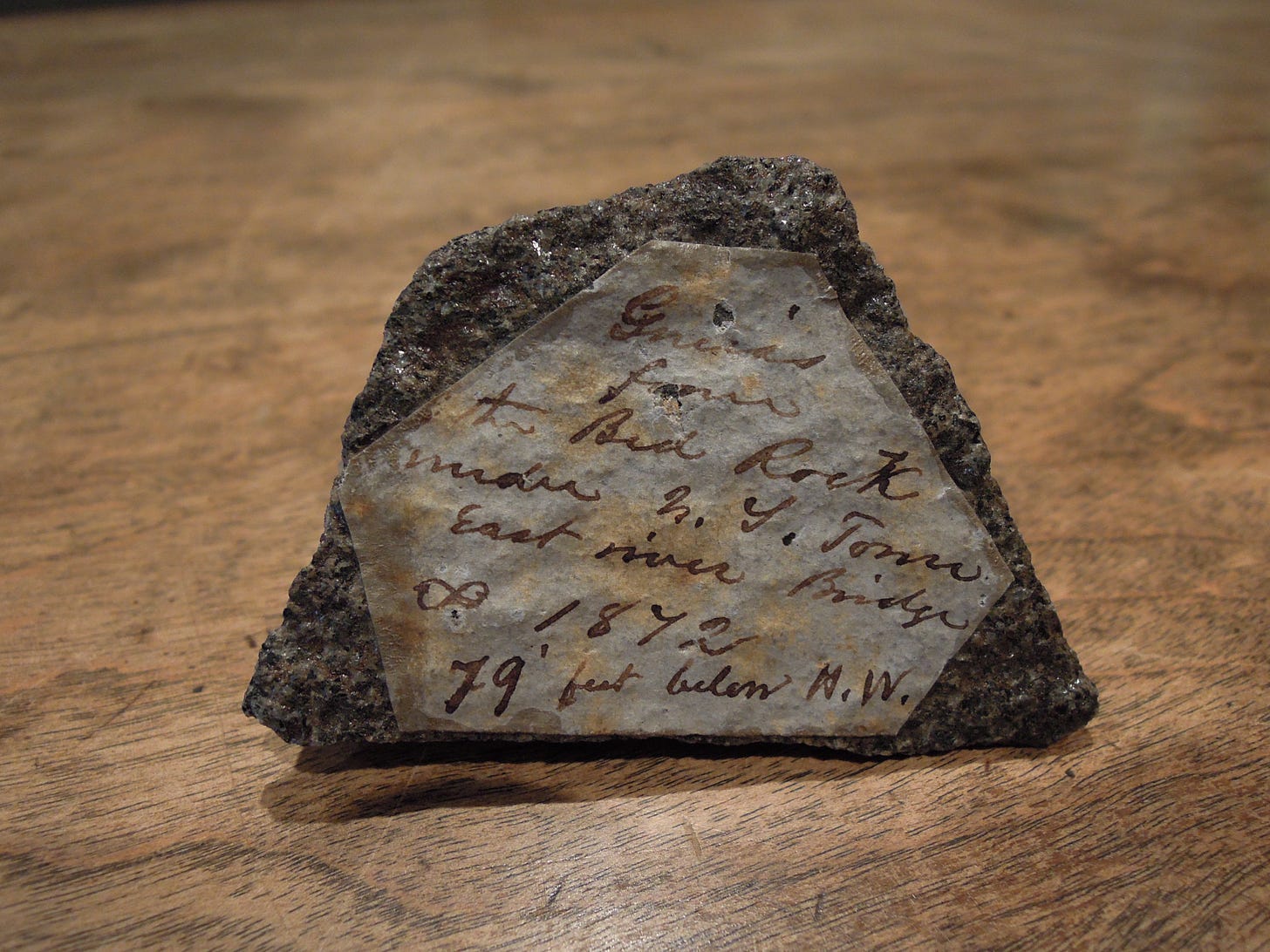

The Brooklyn Bridge has been in the news — two cadets were killed, and many people injured, when a Mexican naval vessel crashed into the bridge on Saturday May 17. The bridge itself, which opened to the public just over 140 years ago, was undamaged; but when work began in 1869 many thought its completion was uncertain or even impossible, for nothing like it had ever been built before. Its construction was fraught with danger, as the following narrative demonstrates. It was also in mid-May that the foundations of the bridge reached their final — and at the time, extraordinary — depth. The ‘caissons’ of the Brooklyn Bridge were chambers deep beneath the river’s surface: it was a brand-new, dangerous technology. As the tower climbed, the caisson sank, the riverbed dug out by men working in compressed air. At the time the effects of compressed air on the body were not understood. Washington Roebling himself, along with many of his men, was badly affected by the condition. Next time you cross the Brooklyn Bridge, consider the remarkable decision made by a single man on a single day in May.

*

The first real caisson was constructed in a coal mine in the Loire Valley by Charles-Jean Triger; and here, in 1840, the first medical observation of “the bends” — so called because of the twisting agony it caused in its victims — were made. Two physicians, B. Pol and T. J. J. Watelle, noted the “severe pains in the arms and knees” suffered by some of the men; they would also observe that On ne paie qu’en sortent, “one only pays on leaving”. It wasn’t being down in the caisson which caused the problem: it was coming back up into normal atmosphere. They were also the first to suggest that a return to the compressed air would effect a cure. Decades later, in Brooklyn and New York, Washington too would note that this “heroic mode” of returning straight down into the pressure would alleviate the “intense pain” the condition caused. “The fact remains, however, that the effects of compressed air on the human system constitute the principal difficulty attending deep pneumatic foundations,” he wrote in 1872.

Andrew H. Smith, a physician hired by Washington Roebling to look after the men working down below, had been carefully observant of the strange effects of the disease: pallor of the skin, caused, he surmised, by decreased circulation to the surface of the body; for the same reason the fingertips would appear shrunken, as if the hands had been soaked in water. The men suffered pain as if they had been “struck by a bullet”; “as if the flesh were being torn from the bones”. Washington had written in his notes for the caissons that everything must be built “strong enough for a pressure resulting from a depth of 100’, to which it may be necessary to go.” In late April a German called John Myers died; and then a 50-year-old Irishman, Patrick McKay, after he was found “sitting with his back against the wall of the lock, quite insensible.” Washington would note that while the deaths were regrettable, “the number has been much less in proportion to the number of men employed than upon any similar work”.