Sandeels, censorship, and Bob Dylan goes electric

With Ben Okri, Katrina Porteous, and Lizzie Broadbent

Almost exactly two years ago a small London theatre – once a bus station – put on an adaptation of a chapter from my first book. The Lapwing Act was a pretty experimental installation. My friend Dom Bouffard created a haunting soundscape with found objects, Matt Feldman, a young American filmmaker, spun a remarkable world in 16mm, and Jack Taylor, a sculptor and picture framer, made birds out of plaster on the stage. It was messy and noisy. Some people loved it and I’m very aware that others didn’t get it at all. ‘But that,’ Dom Bouffard said to me after the last night, ‘is exactly what art should do. If everyone likes it, you haven’t been brave enough.’

I thought about Dom yesterday while watching the new Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, starring Timothée Chalamet. The closing scene tells the story of the Newport Folk Convention, where the crowd famously erupted when Dylan came on with an electric band. People threw things and Pete Seeger reportedly threatened to put an axe through the mixing deck. The whole thing is probably overhyped but there’s no doubt that lots of folkies weren’t happy.

There’s a lot to be said for trying to create work that people like. After all, ‘I didn’t think much of that’, is inevitably a fairly galling response for an artist or a musician when they’ve spent a lot of time on something. And yet, to evolve creatively you’re going to have to upset people. There is no avant-garde without ruffled feathers.

It’s a real privilege to have Ben Okri writing short fiction for Boundless. There is something dreamlike about his style and his place in the post-modern British literary canon is well deserved. He is, like so many greats, an example of what can be done if we think originally and go where impulse takes us. Rather than following the crowd.

Patrick Galbraith

Editor

*Please forgive us for sending this again – Sadia Nowshin who ordinarily sends it is at Kew Gardens and Patrick Galbraith added the links incorrectly

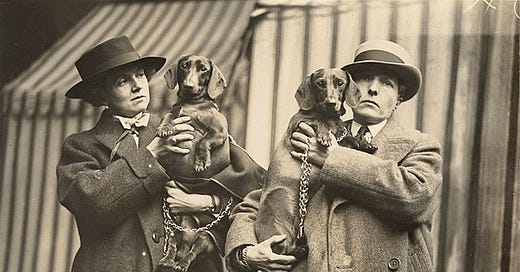

The female literary agents who saved Modernism

Lizzie Broadbent on sex, censorship and the hidden role of women in one seminal year

For anyone interested in censorship, 1928 was a landmark year in literature, with the publication of two ‘shocking’ and ‘obscene’ books that would both end up on trial. Standing in the shadows supporting Radclyffe Hall and D.H. Lawrence through the tumult were their literary agents, Audrey Heath and Nancy Pearn, both powerful forces in publishing in the inter-war years. Theirs are just two of the many stories told as part of ‘Women Who Meant Business’. The project researches the lives of commercially successful women born in the Victorian era whose achievements challenge perceptions about what was possible a century ago.

The 1870s saw the emergence of the first professional literary agents. Heath believed all writers could benefit from a trusted relationship with an agent. New writers gained a hearing from publishers, and protection from exploitative contracts, while seasoned authors could immerse themselves in their craft without the distractions of negotiations and administration. The increase in leisure time, proliferation of consumerism, and advances in printing technology created a boom in publishing and advertising in the 1890s. As demand for written content grew, literary agencies in the UK flourished.

These new industries were largely free from the protocols, traditions and vested interests that held women back in the professions, engineering and the civil service and so provided fertile ground for women with ambition. Any woman with a good secondary education could start as a secretary, prove her worth and spot opportunities for progression into commercial roles. Heath and Pearn, both followed this trajectory, and worked their way to the top.

Lizzie Broadbent is the founder of Women Who Meant Business, a project celebrating pioneering business women

The vulnerability of life

Katrina Porteous, the T.S. Eliot shortlisted poet, on sandeels and false springs

A flash of silver catches my eye. Ten centimetres long, narrow, straight, a bright tube of tin foil lies on the sand at my feet, at an angle to the tide’s fizzing edge. I bend to peer at it. A pale blue sequin pinned by a deep black dot stares back at me. There is a moment’s frisson: life recognising life. The sequin gazes from a tapered head, a body delicately zigzag-patterned with the faintest oily sheen of pink, lilac, turquoise. The sandeel looks vivid, almost electric, but it does not move. The tide is not coming back for it.

It is one of those ‘midwinter spring’ mornings, when the light feels strong, and as I set off on my walk there’s a tremendous, energetic chatter of starlings on wires and sparrows in hedges. Is it spring yet? Is it? Is it? It’s cold, but out of the keen north wind there’s a perceptible warmth in the sun. We all know the two steps forward, one step back dance of spring. February and March will bring its ‘lambing storms’; snow, rain, gales. But dawn comes earlier and the nights are noticeably lighter now.

Katrina Porteous' fourth poetry collection, Rhizodont, was published by Bloodaxe Books in June 2024 and was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot prize

Three stone columns

A short story by the poet and novelist Ben Okri

One day I went down to the beach and saw a man building pillars with small stones. They were like dolmen. He built three pillars. He erected them to amuse his children. He constructed them on the edge of the sea where the beach sloped up towards the walls of the nearest houses.

I watched the Greek man as he carefully put a rough stone on a smooth one, an angled stone fitting onto a hollowed one. He had put about ten stones on top of each other. His children had helped him fetch stones. Patiently he had built this little stone structure like something you might see at Stonehenge, except his were very small. When he had finished, the three pillars stood solid. Not the waves pounding the beach, nor the strong winds blowing from over the Mediterranean could topple them.

By the evening the Greek man, his wife, and kids were gone. Only the mystery of the perfect stone pillars was left behind on the beach.

Ben Okri’s new book Madame Sosostris & the Festival for the Broken-Hearted will be published next month by Bloomsbury